Art & Culture

Caravans of Gold

Last week I went to see Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture, and Exchange across Medieval Saharan Africa at the Block Museum. The Block Museum is located on the Northwestern University Campus, and its exhibits are stellar. I’ve been to a few but should be more diligent about visiting this free treasure trove of cultural learning.

“Caravans of Gold is the first major exhibition addressing the scope of Saharan trade and the shared history of West Africa, the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe from the eighth to sixteenth centuries.Weaving stories about interconnected histories, the exhibition showcases the objects and ideas that connected at the crossroads of the medieval Sahara and celebrates West Africa’s historic and underrecognized global significance.”

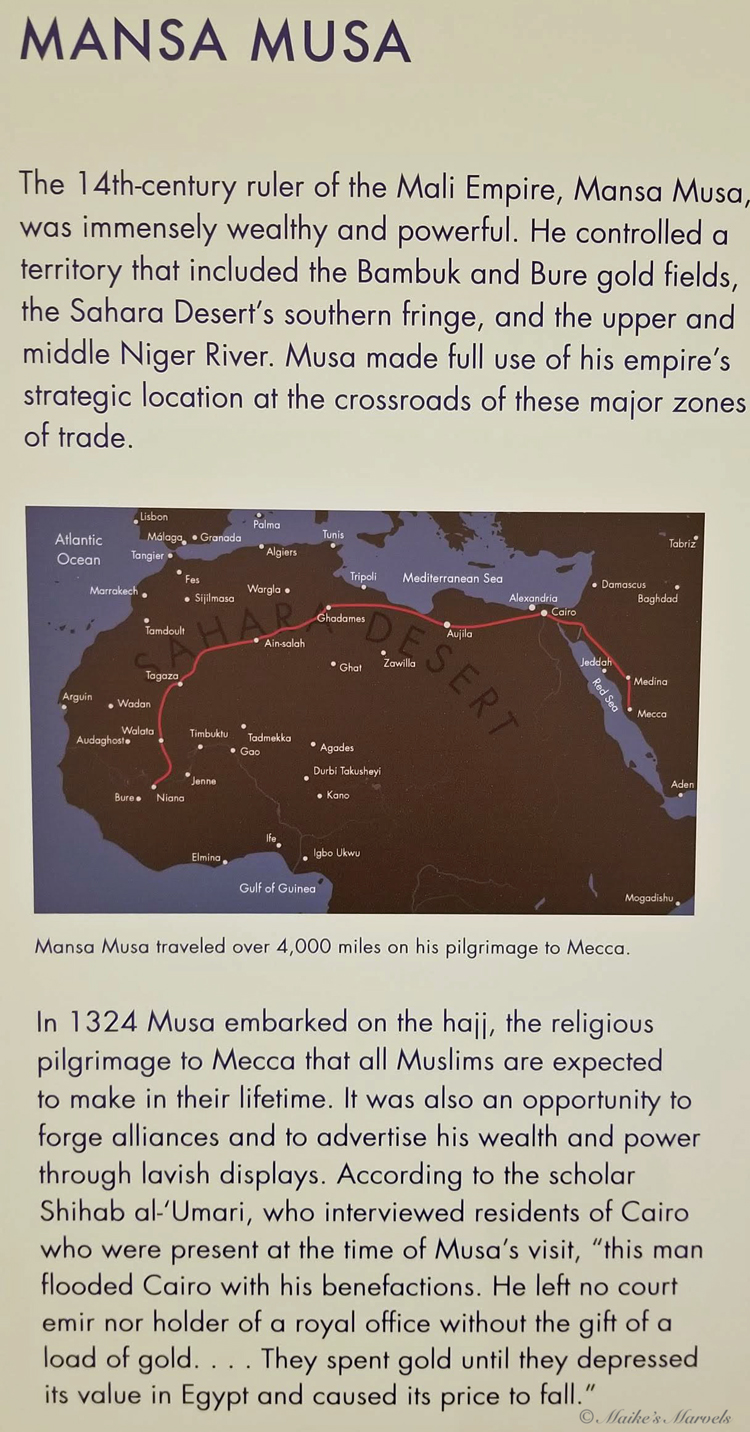

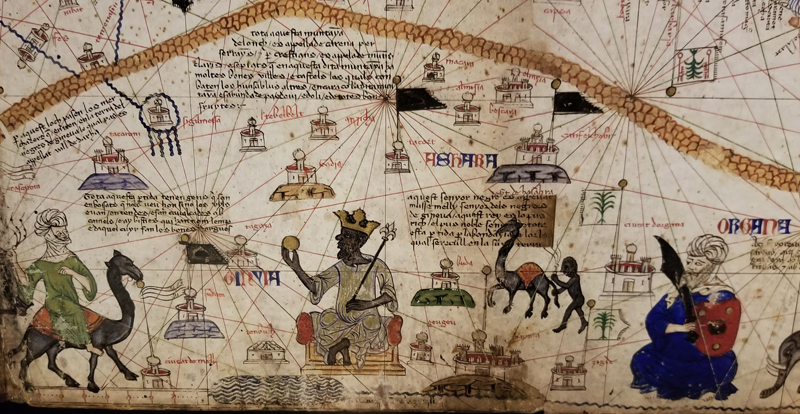

This exhibit holds at its core a pilgrimage of Mansa Musa, the King of Mali, who made his trek to Mecca with 300 pounds of gold carried by 8,000 courtiers, 12,000 slaves, and 100 camels. He is (the only person of color) depicted in the Catalan Atlas, highlighting his importance as the richest man ever.

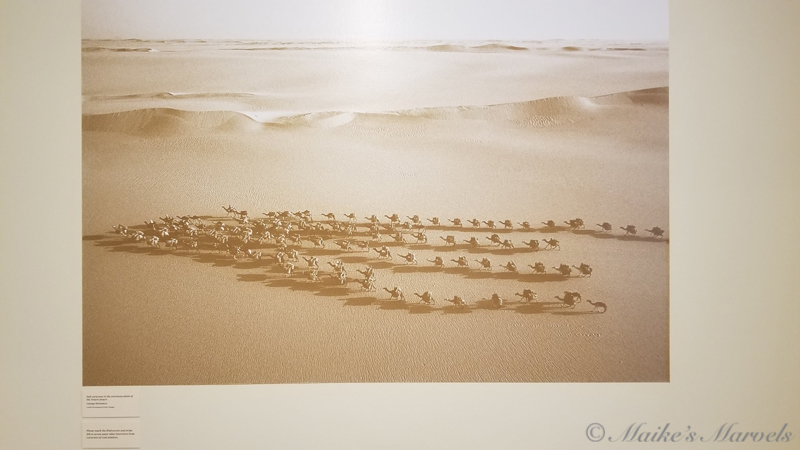

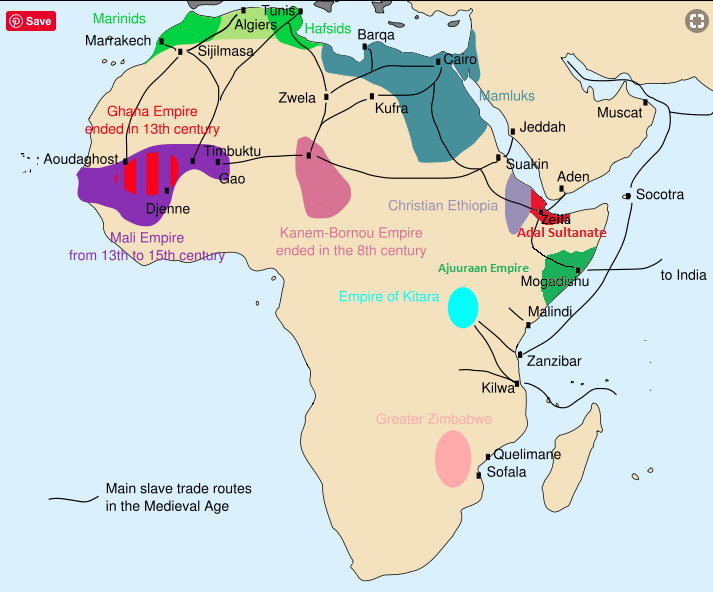

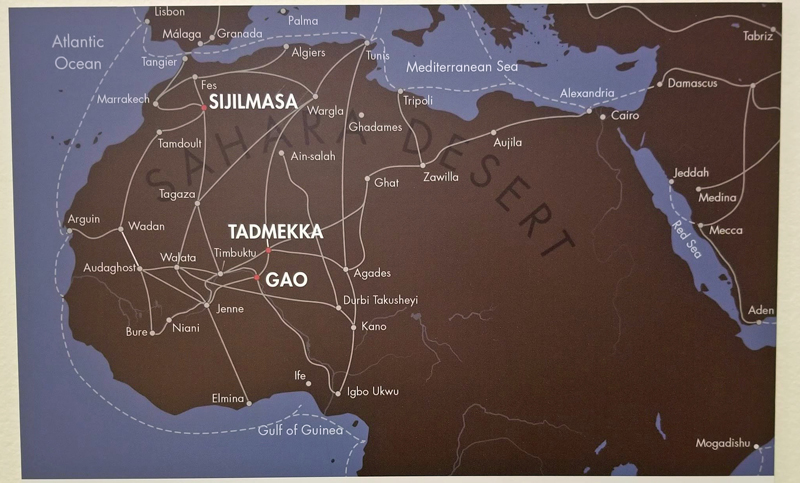

Africa’s medieval period began with the spread of Islam in the 8th century and ended in the 15th century with the arrival of Europeans. During this time the Sahara desert was the center of a global network exchanging commodities such as gold, salt, and slaves. The Saharan trade route also carried copper, glass beads, ivory and textiles.

A camel traveled 3 miles per hour and the Saharan trade route spread over 2500 miles. Navigation was done with Astrolabes, this one is from 1236/37.

West African gold was coveted for its purity, and the exhibit holds artifacts depicting its use in coins, jewelry, religious artifacts and fabrics. Dinars were invented in the 7th century by the Umayyad Caliphate. Their gold was struck at Sijil. Bald dinars were molded in the 10th and 11th century in Tadmekka. Also on display were florins from 1252/1303 and gold fittings from the 10th/11th century. Rock salt was mined in the Sahara and very scarce in West Africa, making it a currency of its own.

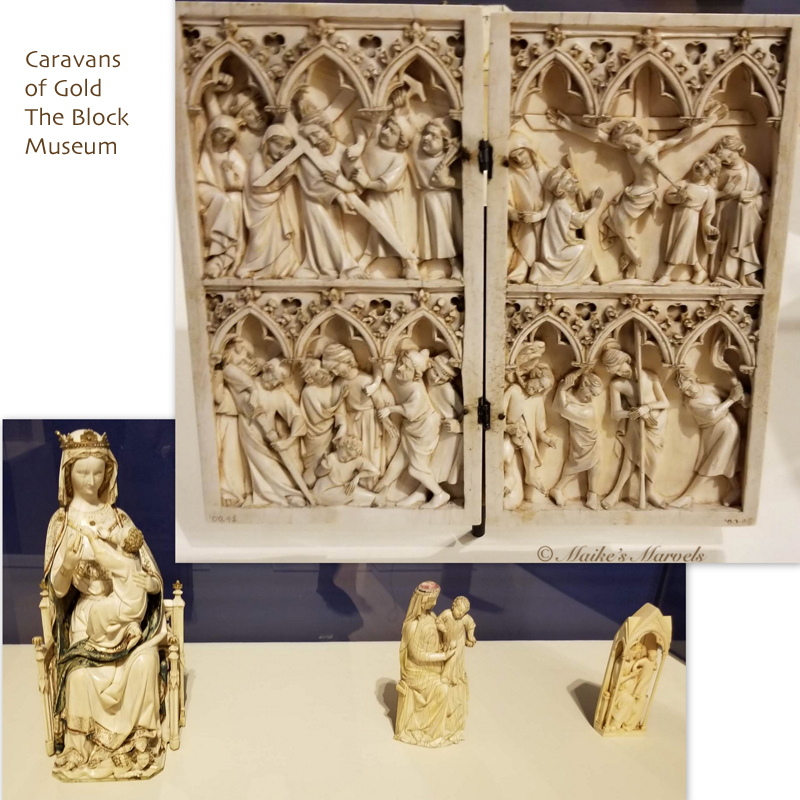

One plaque explained that gold was associated with the divine realm. Gold was hammered into thin sheets of gold leaf. Areas to be guilded on the wood panel were coated with bole (reddish clay) as an adhesive, on which the gold leaf was burnhished. Then the gold leaf was incised or stamped. The candle light reflected on the art in a dark church created a sense of heaven on earth. Look at this gorgeous triptych calledCoronation of the virgin, 15th century Italy: Tempera and gold on panel.

Tapestries utilized gold and silver silk from Africa.

In the 12th century, a record indicates that sugar was transported to Tunisia and Byzantium, along with indigo, aluminum, brass, gold, male and female slaves, ivory, ebony, elephant tusks, reeds and oryx hides.

Slavery in Africa differed from colonial slavery. At the Field Museum I learned that slaves still had a community and the ability to bring grievances up to a public forum. I am still fuzzy on who started it, but it is clear that the treatment of slaves vastly deteriorated once they were placed on the ships of the Portuguese, British, and the Dutch. Transatlantic slavery continues to hold repercussions. Map by Runehelmet derived from Aliesin – File:Traite_musulmane_medievale.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0

As a jeweler I was fascinated by the beads from the 8th to 13th century (which we weren’t allowed to photograph). Beautiful glass vessels were not much different from what my artisan friends create today. Lusterware was innovated by Arab potters who added silver sulfides and copper oxides to their glaze in the 11th century. I love these whimsical animal depictions and wonder who made them.

Stylized horseman sculptures indicate the need for a calvary for expansion. I wish we knew the artisan group that created these.

Oryx Hide Shields like this one from the early 20th century were traded across the desert and depicted on art in the 13th century.

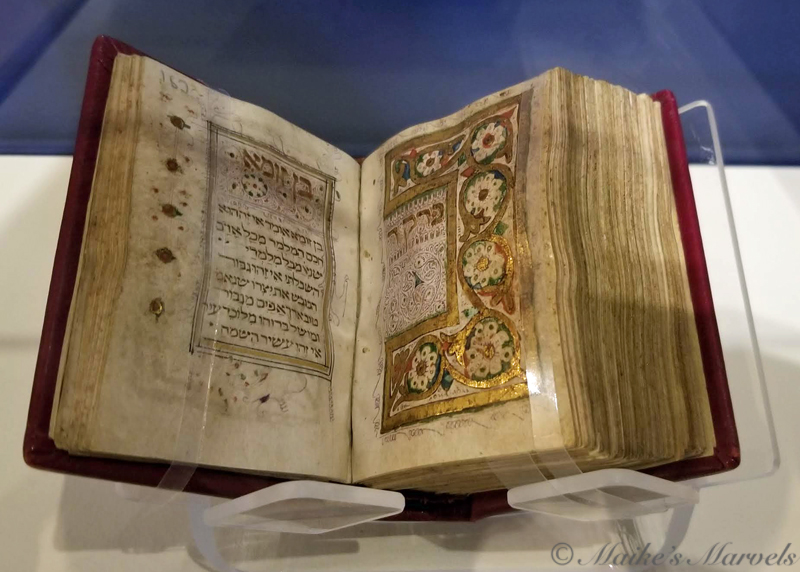

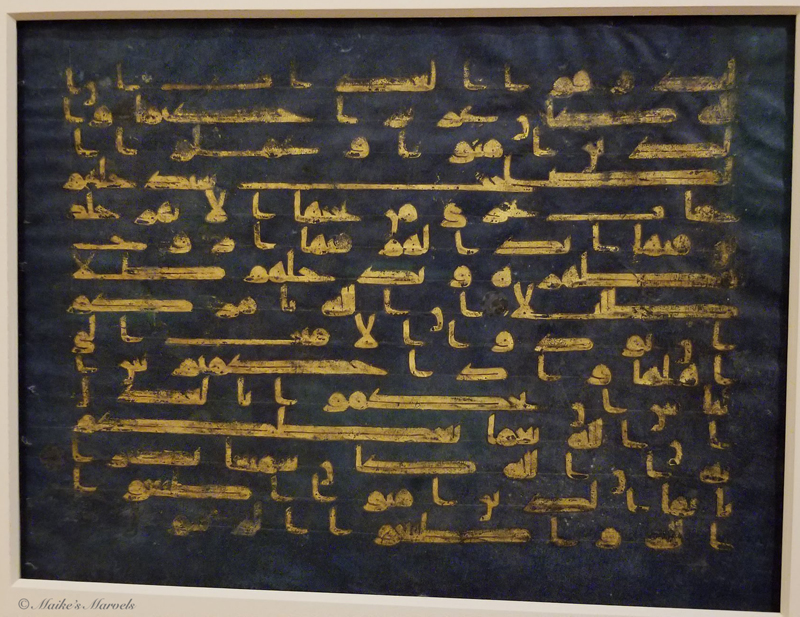

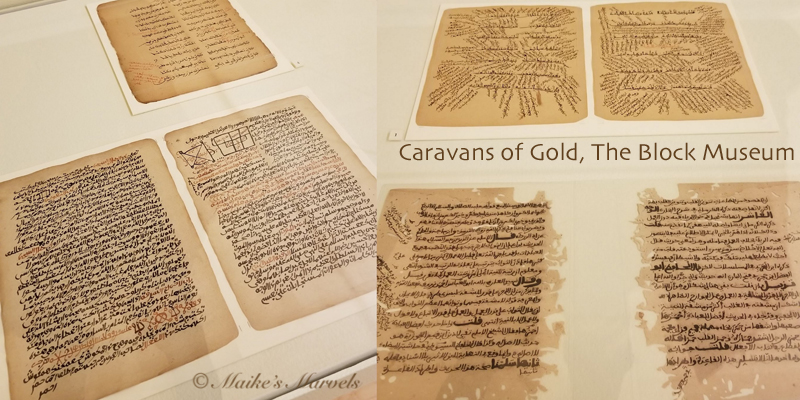

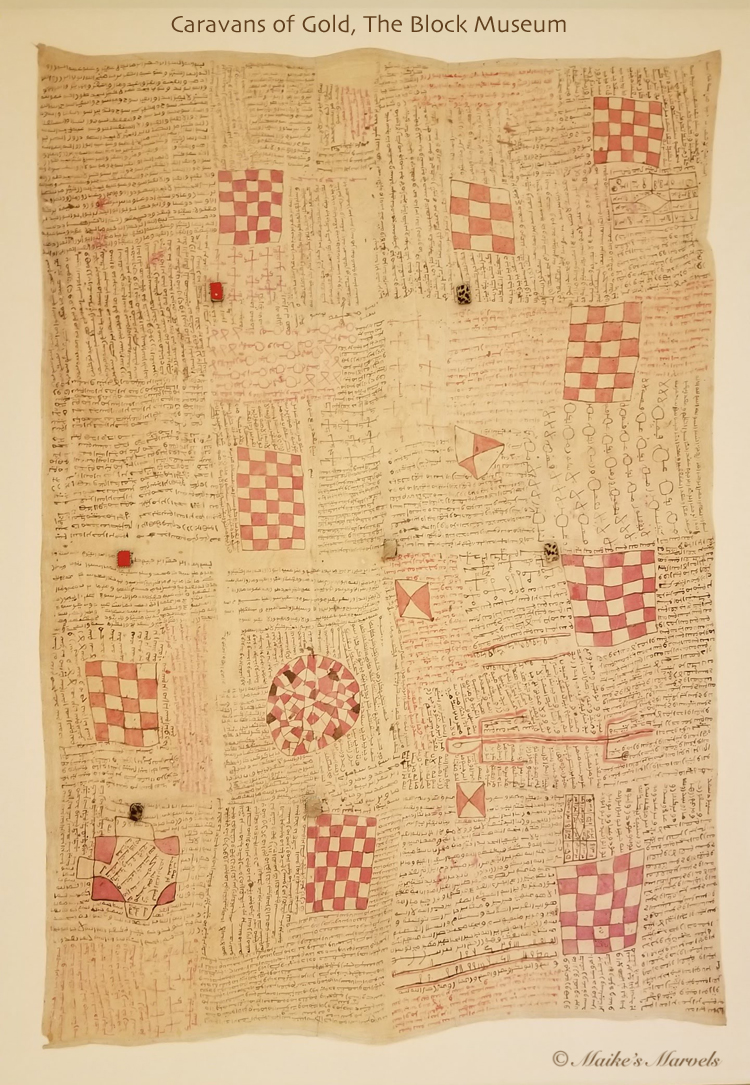

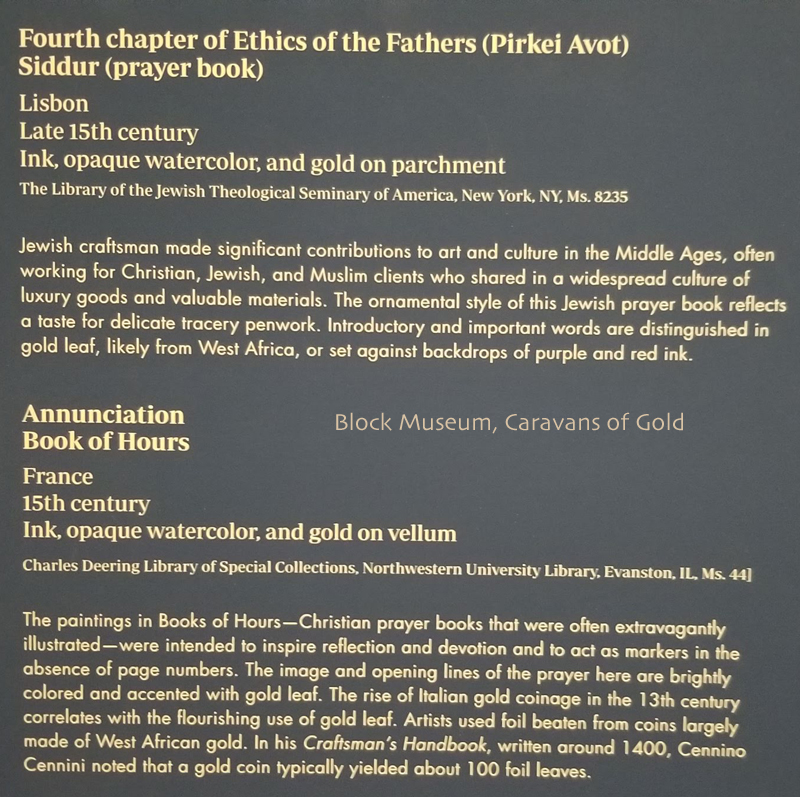

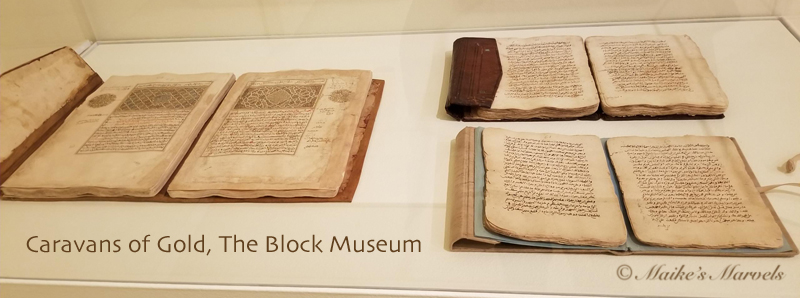

“During the medieval period, a shared manuscript culture among Muslims, Christians, and Jews extended across North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Characteristics included elegant calligraphy; painted embellishments…; gold accents; and decorative leather bindings. The gold and leather used in books were imported from West Africa, and book culture likewise spread to West Africa as Islam spread across the Sahara Desert,” according to the plaque.

Indigo pages sound so dreamy and were quite luxurious. This leaf is from the Blue Qur’an, dated 9th/10th century from Iraq, Iran or Tunisia, and is gold and silver on indigo-colored parchment.

Other manuscripts on display were from the Tarikh al-sudan and Tarikh al-fattash.

I love the margin notes and ‘scribbles’ in these pages, that span a variety of subjects. We were also introduced to Leo Africanus and his Italian description of Africa in 1526.

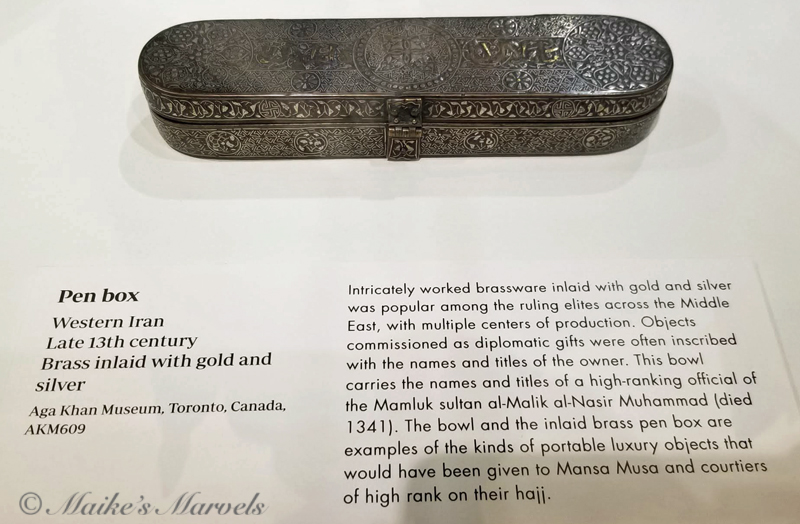

Of course writing utensils needed storage cases too.

According to the exhibit: “The activation of the words of the Qur’an for protection and healing is a widespread Islamic practice.” This is a Talismanic Textile with passages from the Qur’an and amulets attached to it for therapeutic intent is dated late 19th/20th century from Senegal.

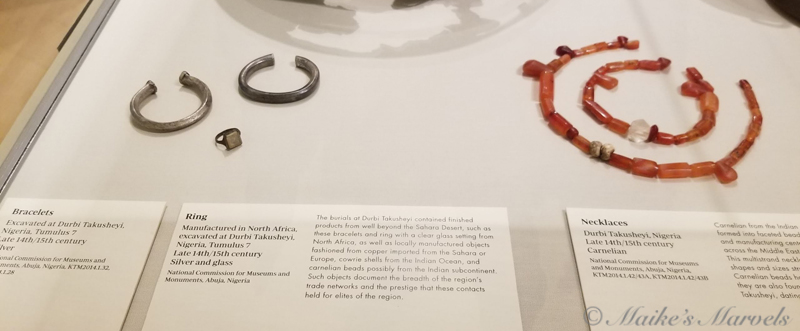

Jewelry also served as amulets. The bracelets are inscribed in tifinagh, which predate Arabic inscriptions. This language paved the way for the adoption of written Arabic.

Ivory tusks were traded for copper in Northern Europe starting in 1230. Originally the outsides of the tusks were carved until the interior of the tusk proved more artistic.

The Nigerian Nok Culture flourished at the same time as Egypt and Classical Greece. They traded a vast amount of stone and glass beads, including carnelian, jasper and quartz. This is a pendant of a bird and two eggs from a shrine storehouse in Igbo Ukwu, 8th/early 11th century: leaded bronze, copper wire, glass.

The figurines on display were amazing. The trade in necklaces and beads is reflected in the embellishments on these figures.

A shell was made of leaded bronze.

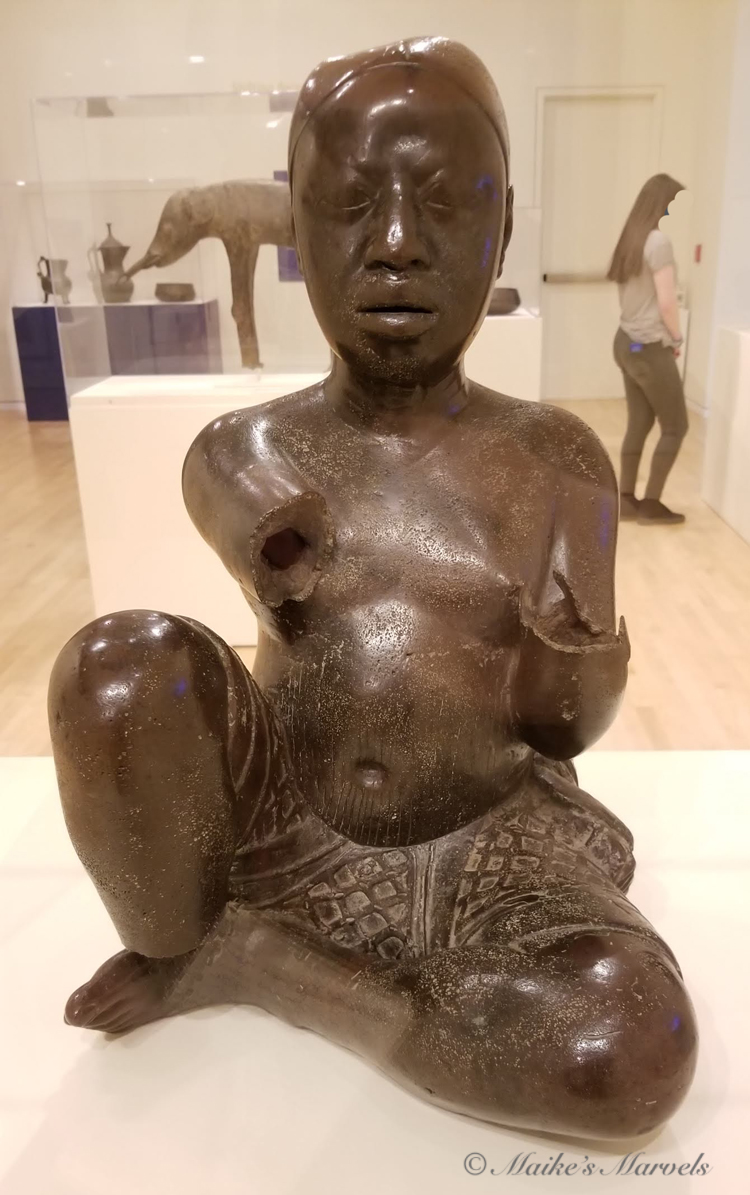

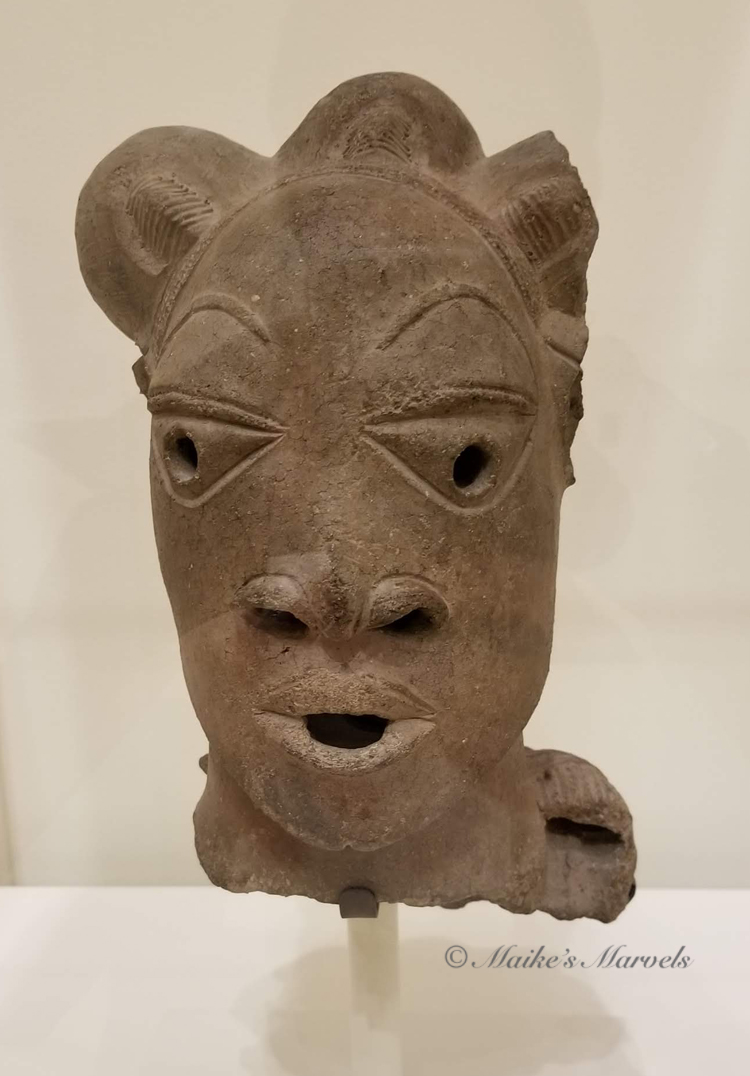

Then the figures from Ife in central Nigeria caught my eye. They used terra cotta, copper and copper alloy to cast their sculptures. The copper ores were mined in France. Copper was alloyed with arsenic, lead, tin or zinc to make brass. This seated figure was figure made out of copper, arsenic, lead and tin.

These portraits had me wondering about the defacing of noses on ancient statues. There is a theory that this was to hide the African features of these historic powerful figures, rather than just religious reasons.

I was mesmerized by the intricacies of this Bowman from Jebba Island, Nigeria made from copper alloy in the 14/15th century. The statue indicates that cowries from the Indian Ocean were used as currency in medieval West Africa. To see this outfit in real life!

Fabrics had a distinct sewing style that was eventually carried on by Amazigh women and Fulani men. an artifact in the modern section of the exhibit indicates that these weaving styles echo the historic garments on display in the exhibit. The Tellem Textiles are narrow strips sewn together edge to edge. These textiles are made from cotton cultivated in Western Sudan.

The exhibit also addresses the inland Niger Delta, where the Niger river cultivated a variety of trade hubs in the fourth century CE. Ghana was an established multilingual hub in the 7th-13th century, Mali during the 13th-16th centuries, and Songhai held power during the 14th to 16th centuries. Caravans of Gold draws on recent archaeological discoveries, including rare fragments from major medieval African trading centers like Sijilmasa, Gao, and Tadmekka.

The exhibit drew heavily on the Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History to place artifacts into context. The exhibition features loans from partner institutions in Mali, Morocco, and Nigeria that span five centuries. In the 14th century, silver and carnelian continued to entice with beautiful jewelry created and traded, and also placed in burial sites.

The late 15th century brought a shift in trade to Africa’s Atlantic coast as ship trade became more predominant. This did result in more artifacts from a shipwreck that shed additional light on African goods in that period. Caravans of Gold, Fragments of Time is curated by Kathleen Bickford Berzock, Associate Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Block Museum and remains on view until July 21, 2019 in the Main Gallery at 40 Arts Circle Drive in Evanston.

My mind is still reeling from all this beauty, but I now want to put it in the context of the Western History I was brought up with. ‘Civilization’ and ‘culture’ completely redefines itself in this new context.

The Block Museum exhibition will travel to The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto (Sept. 21, 2019 – Feb. 23, 2020) and then to the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institute (April 8 – Nov. 29, 2020)

Brigitte Meier, Denninghoff, Reihe IV, 1964